John R. Kelso’s Civil Wars:

A Graphic History - 1863

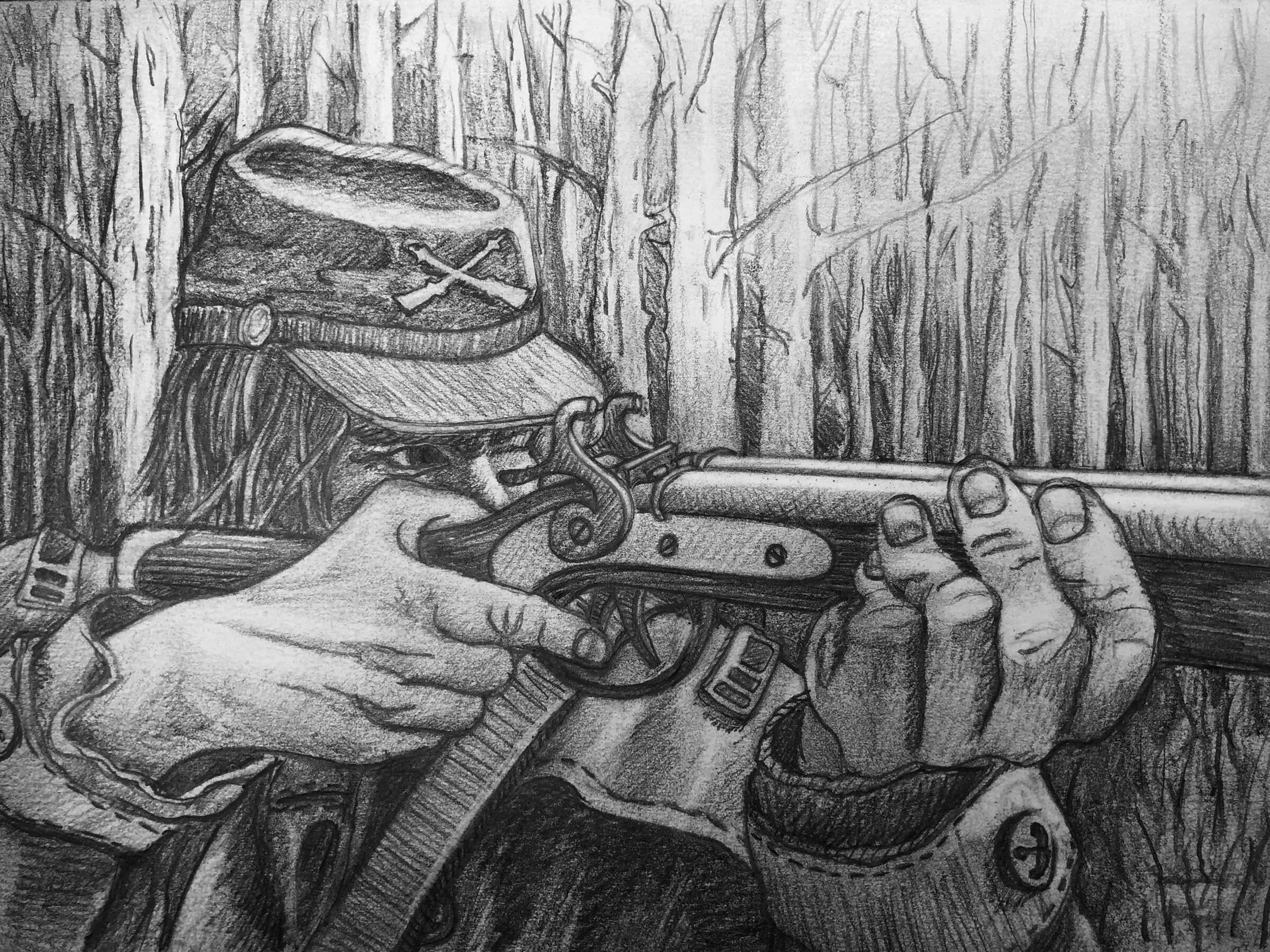

15. THE BATTLE OF SPRINGFIELD

Jan. 8, 1863. Kelso’s detachment had been racing up from northern Arkansas to Springfield, an invading force of several thousand Confederates commanded by Gen. John S. Marmaduke right behind them. Springfield was a crucial military depot, but it was weakly defended: including green militiamen and hospitalized soldiers, it had about 2,300 men. The town’s defenders hurriedly pierced walls for musket fire, stocked the two forts with provisions, and refurbished some old cannons. Civilians hid their money and headed for their cellars. A newspaper reporter summed up the general feeling: we won’t give up the town without a fight, “but we shall probably be whipped.”

The battle began at 10:00 a.m. as rebel artillery opened fire. Cavalry—including Kelso’s squad on the eastern flank—began skirmishing, and rebel infantry began moving into the southern part of town. The attackers advanced by crawling “like Indians,” the reporter said, “from one stump to another, sheltering themselves as much as possible, but keeping up the deadly fire.” As the rebels pushed closer to the town center, a dozen men died in a few moments in a fight over a cannon. In the east, Kelso and his men were nearly cut off when a larger rebel cavalry swept in. By nightfall, the Confederates occupied the lower third of the town.

The main fighting had stopped, but the artillery shelling continued. Sent out as a scout, Kelso crept onto the dark battlefield among the dead and wounded as shells continued to pass overhead. When a Confederate ambulance wagon came by, he held his breath, face in the cold dirt, pretending to be dead.

Then the shelling stopped and Marmaduke’s forces withdrew. In the grim bookkeeping that followed, Union commanders reported 14 killed and 146 wounded, though another dozen would die from their wounds in the days that followed; Marmaduke reported 19 killed and 105 wounded, though a Springfield physician knew of 80 Confederate burials. Springfield remained in Union hands.

16. HERO OF THE SOUTH WEST

Unionists called Kelso “The Hero of the South West.” Stories about him spread. He was part of expeditions of as many as 200 men against enemy bases in northern Arkansas and helped lead strike forces of 60 riders against guerrilla hideouts. With squads of 10 men, he attacked small outlaw camps. Sometimes he would charge a bushwhacker cabin by himself. Unionists celebrated his daring and courage. Secessionists called him a ferocious “rebel-killer” who “butchered his victims” with an “unforgiving heart.”

Once he went out alone into the Ozark Mountains, disguised as a bushwhacker. He joined a rebel camp, but most of the bandits left him behind with two who did not trust him—they “never took their hands off their guns for a moment.” Kelso, chatting with them affably, pretended to have a splinter in his finger and held out his hand for them to see. As they leaned forward, “each let the butt of his gun drop to the ground.” In a flash, Kelso “seized the gun of the nearest bandit” with one hand while drawing his revolver with the other and shooting both rebels.

Another time, Kelso and his men surrounded a house. He “saw three bandits within, and keeping his eyes on them and his hands on his shotgun in the position of ‘ready,’ crossed the fence and started for the door.” As he did so, “a big dog came snarling and growling at him and seized him by the calf of the leg. Not in the least disconcerted by this unexpected attack of the dog, he stopped, and keeping his eyes on the bandits took with his right hand his revolver from the scabbard, and feeling for the dog’s neck shot the beast dead. He proceeded as if nothing had happened.” Seeing this, the bandits fled without firing a shot.

17. WOUNDED WARRIOR

Kelso became known for riding his charmed claybank horse, Hawk Eye, and for carrying an extra-large shotgun. Yet when his luck finally evaporated in the late summer of 1863, it was a shotgun blast and an accident with Hawk Eye that gave him injuries that would trouble him the rest of his life.

Kelso and his men were galloping after three bushwhackers. As a rebel turned to fire his shotgun, Kelso instinctively slid to the right on his saddle and was hit “slantingly.” He “felt the shots, like heavy hot irons, tearing through my flesh on my left breast and in my left hand.”

Only later, after the bushwhackers and one of Kelso’s own men had been killed, could he assess his injuries. He had fifteen wounds. A bullet lodged in one of his fingers would leave his left hand partially disabled. The shots in his chest “looked like a cluster of ugly blue bumps,” causing inflammation and pain. So he took his pocket-knife and cut them out. But he missed one, he would come to think. Lodged beneath his sternum, it would, he believed, fester for years and eventually kill him.

A month later, Kelso was galloping in pursuit of another band of bushwhackers. His picket rope fell to the ground and got tangled in Hawk Eye’s legs. Horse and rider did a somersault. “The great weight of the horse . . . crushed me to the earth, rupturing me badly in the right groin, partially dislocating my hips, and seriously injuring them in the joints. My left shoulder was also severely injured, my head and left ankle severely bruised.” These injuries, too, would never fully heal.

But he refused to be kept from the field. He had to be carried to his horse and placed on his saddle each morning, and then carried from his horse and placed on his blanket each evening.

18. THE DEPARTED

Kelso had written a short note to his wife Susie in late February 1864, “worn out from a long and toilsome scout,” his hand “so unsteady” that he could barely write. There were many more long and toilsome scouts through the first half of 1864. He had been promoted to captain and had launched his political career. But as the war dragged on, good officers, well-intentioned and able, could make mistakes, and men died. Brave soldiers, doing their duty, could be just a step wrong or a second slow, and men died. In August, a year to the day after he had been seriously wounded, he was still fighting in battles “where the bullets flew thick as hail” and seeing “several of my brave boys fall mangled and bleeding around me.” He mourned the dead and was weary of mourning.

Exploring the hills in northern Arkansas, Kelso and his men came across the trail taken by “a considerable party of Federals” that had been ambushed and “cut to pieces” a few months before. Kelso found the body of a soldier. “He sat with his back against a tree, his right elbow resting upon his right knee, and his right cheek resting upon his right hand. He had evidently crept to this place mortally wounded, and had died sitting in this position.” He still wore his uniform, “but his garments hung very loosely upon him, for his flesh was now all gone except for the cartilage that held the bones together. In the bones of his left hand which rested by his side he clutched a faded photograph. It was that of a beautiful woman, with [a] happy smiling face.” He slipped the photograph back into the soldier’s hand “and left him as I found him.”

19. THE CHEROKEE SPIKES

Known for executing their prisoners, in March, 1863 Livingston’s Cherokee Spikes had captured two men in Kelso’s regiment who were outside the stockade at Granby, tending to a sick family. The guerrillas shot the soldiers as they begged for mercy. Kansas troops tried to track the Spikes into Indian Territory, but Livingston and his men disappeared.

On May 18 Livingston launched a surprise attack on 60 soldiers from two Kansas regiments, one being the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry. The Cherokee Spikes chased and cut down fleeing soldiers for eight miles, killing thirty and wounding twenty-eight. Nine days later Livingston was writing to Gen. Sterling Price at Little Rock, complaining about Black regiments “who have all the hellish passions belonging to their race” and pleading for reinforcements.

A few weeks after his aborted attack on Kelso’s men, Livingston was killed charging a small group of Union militiamen holed up in a courthouse.

20. AMBUSH

In the late summer of 1864, an expedition of 175 Federals tracked a large rebel force through “an everlasting jungle of brush and weeds.” Up ahead, a six-man scouting party stopped at a horseshoe bend in a creek to let their horses drink. “Instantly the whole semicircle flashed into a blaze, and every man and every horse of [the] heroic little band was riddled with bullets.”

Kelso rushed forward to help the wounded. The worst off was Cpl. “Caz” Thomas. Caz pointed to a wound and asked Kelso if it would kill him, and Kelso had to tell him the truth. A few minutes later, Kelso, weeping, helped carry his dead body away in a blanket.

As the sun set, the MSM began their retreat. Kelso stayed behind to see if the rebels sent any pursuit. “The ground was covered with blood [from] wounded men and wounded horses,” he remembered. “Bloody boots that had been cut from broken legs lay scattered around.” With twilight, the silent forest began to darken. “Several horses were standing there slowly bleeding to death. They stood in great puddles of blood. I went to them, and patted their necks. They looked pleased and grateful. They looked around at their bleeding wounds, and then pleadingly in my face, begging in their poor dumb way for the help which they expected at my hands but which I was not able to give them.” Kelso turned away and started to follow his men. “The poor creatures, seeing that I, their last friend, was deserting them, began to neigh piteously, and to hobble along after me, giving me looks of reproach almost human in their expressiveness. One of them dragged, tumbling along in the dirt, a hind foot that had been entirely shot from the leg except a small strip of skin.” Kelso hurried away, trying not to look back.

21. ELECTIONEERING WITH A SHOTGUN

Admiring soldiers and grateful civilians encouraged Kelso to run for Congress in 1864. But he could only deliver a few speeches before he was sent back out into the field. “My electioneering, therefore,” he wrote, “had to be principally done in the brush, with my big shot-gun, shooting bush-whackers.”

On September 20, 1864, Confederate Gen. Sterling Price and his Army of Missouri moved across the Arkansas line into the southeast. This was no mere raid of a few thousand men. Price was leading more than 12,000 soldiers; he intended to conquer St. Louis and Jefferson City and place the entire state under Confederate rule.

Price marched north and fought at Fort Davidson on September 27. But he turned west before Saint Louis, thinking that city too well-defended, and decided against attacking Jefferson City, too. On October 23 a little south of Kansas City, the Federals routed the Confederates, and Price’s beaten and bedraggled army fled south. With two Federal divisions in pursuit, the rebels swept down along the Kansas border and toward Missouri’s southwest corner. They bore down upon the few hundred militiamen stationed at Newtonia.

Kelso and another scout, Lt. Robert H. Christian, known as “Old Grisly,” were the last two Federal soldiers in Newtonia as Price’s army began flooding into town. Kelso, on a broken-down old horse, waited anxiously for Christian, who was about eighty yards behind. The rebels saw Old Grisly and charged. Realizing that he had lost the opportunity to escape on his exhausted horse, Kelso planned to leap onto Christian’s when the lieutenant rode by. But Old Grisly stopped, turned toward the rebels, and began firing. “The rebels rushed right on, closing upon him as they came. The bullets that missed him, whistled past me.” He saw Christian fall, and learned later that the rebels “scalped Christian’s head and also his chin, which was covered with a long grisly beard.”

Kelso tossed his army hat away and hoped the rebels would mistake him for a bushwhacker. If not, he planned to open fire with both barrels of his big shotgun and then empty his revolvers at the enemy swarming around him. He also thought, “What a strange place this is for a candidate for Congress to be in so near the day of election!”

The rebels did take him for bushwhacker and rode right past him. He managed to make his way back to his own men. A few days later, he won his seat in Congress.

22. THE FINAL SHOT

On March 3, 1865, Ulysses Grant planned the final push to break Robert E. Lee’s defense of Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia. Jefferson Davis still hoped for divine deliverance. Abraham Lincoln, preparing for his second inauguration the next day, also wrote to Grant, telling him how to handle the enemy’s surrender.

In northwest Arkansas on March 3, a woman was angry. She had supported the Southern cause, but the prospect of defeat was not what infuriated her. Some armed Southern men had ridden up to her farm, grabbed all the bacon she had put up after slaughtering her hogs, and made off with all her seed corn for the coming spring planting. So when some Federal cavalrymen rode by not long afterward, she told them what had happened and pointed the direction the guerrillas had taken.

Up a long winding trail, through a ravine, and into some wooded hills, a man sat against a tree, cutting slices of the woman’s bacon. His horse, hitched in front of him, chomped on the seed corn. Suddenly a shotgun blast sprayed the dirt by his boots. Springing to his feet, he lunged to his horse for his gun. The shotgun fired again. One shot went through his head, and he died as he hit the ground.

As Kelso walked from the woods, he tore a piece of paper from his notebook, wrote a note and pinned it to the corpse’s coat. This was a practice the bushwhackers themselves had started. Kelso’s signed note read: “I hereby send my kindest compliments to the friends of this bush-whacker and inform them that he makes twenty-six rebels in all that have fallen by my hand. I had vowed to kill twenty-five. I have more than fulfilled my vow. I am content.” On his last scout, it was the last shot fired and the last kill by Congressman-elect Kelso in the Civil War.