The Wild West: Modesto, California

(Adapted from Teacher, Preacher, Soldier, Spy, 353-60).

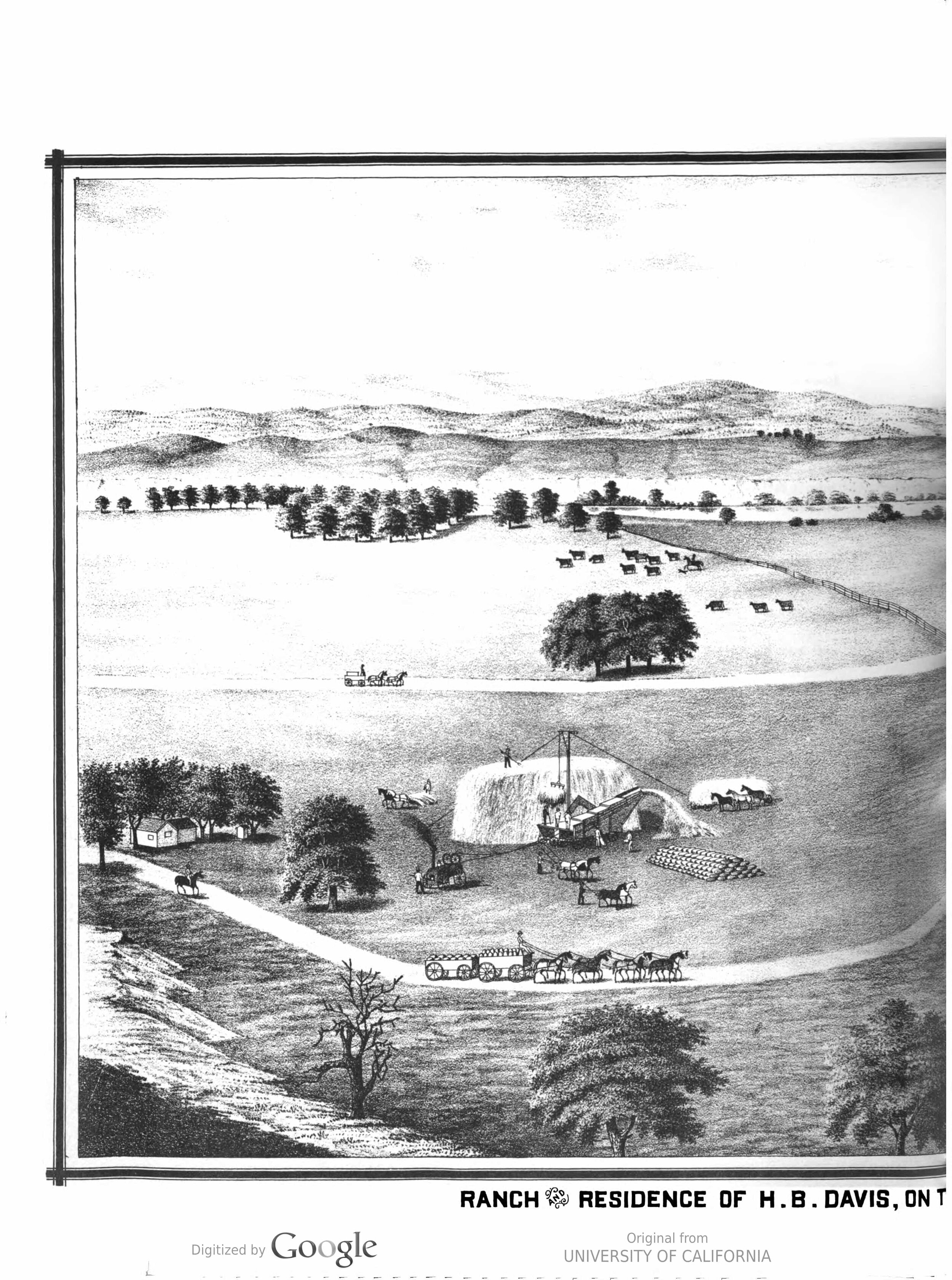

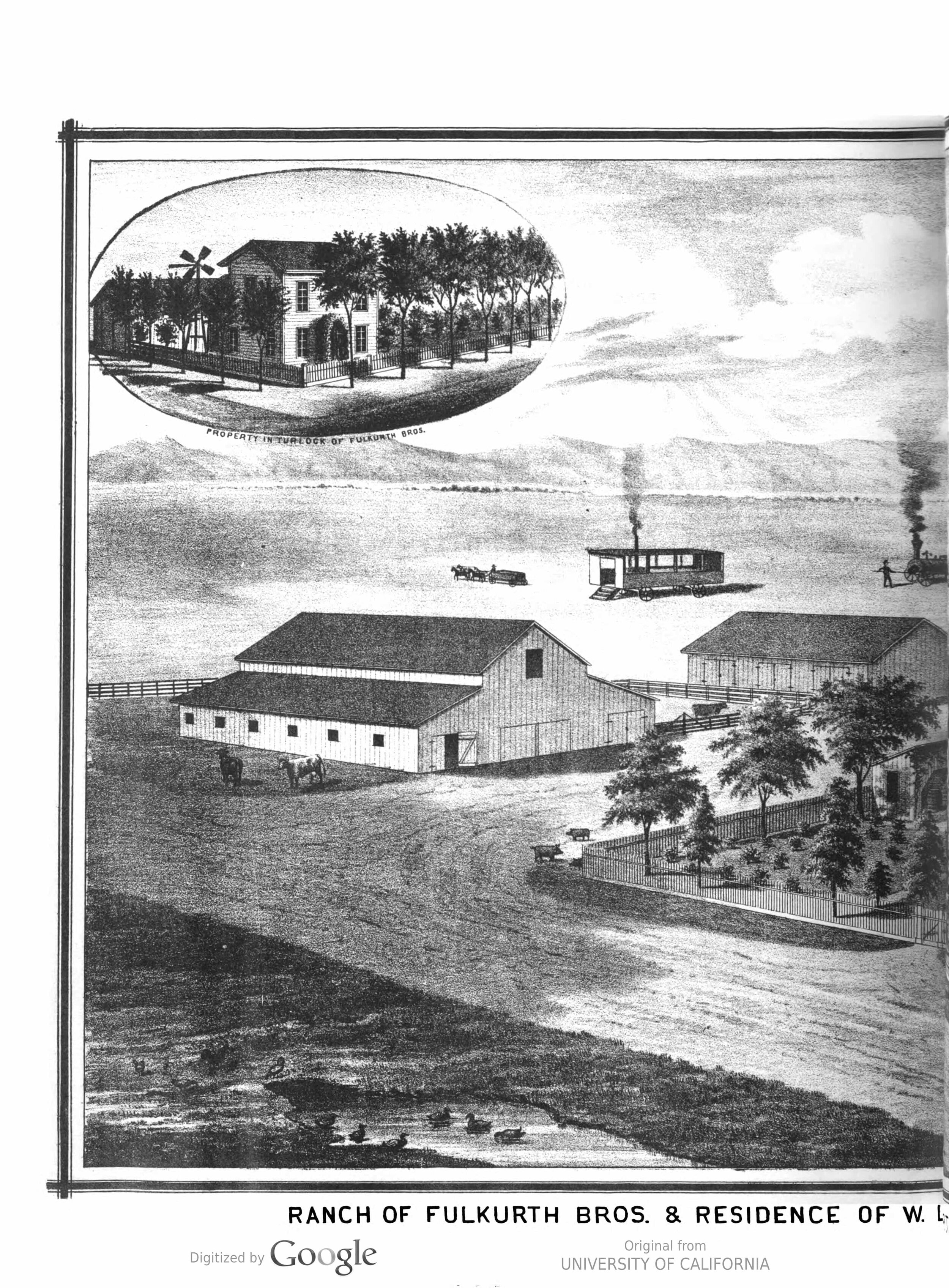

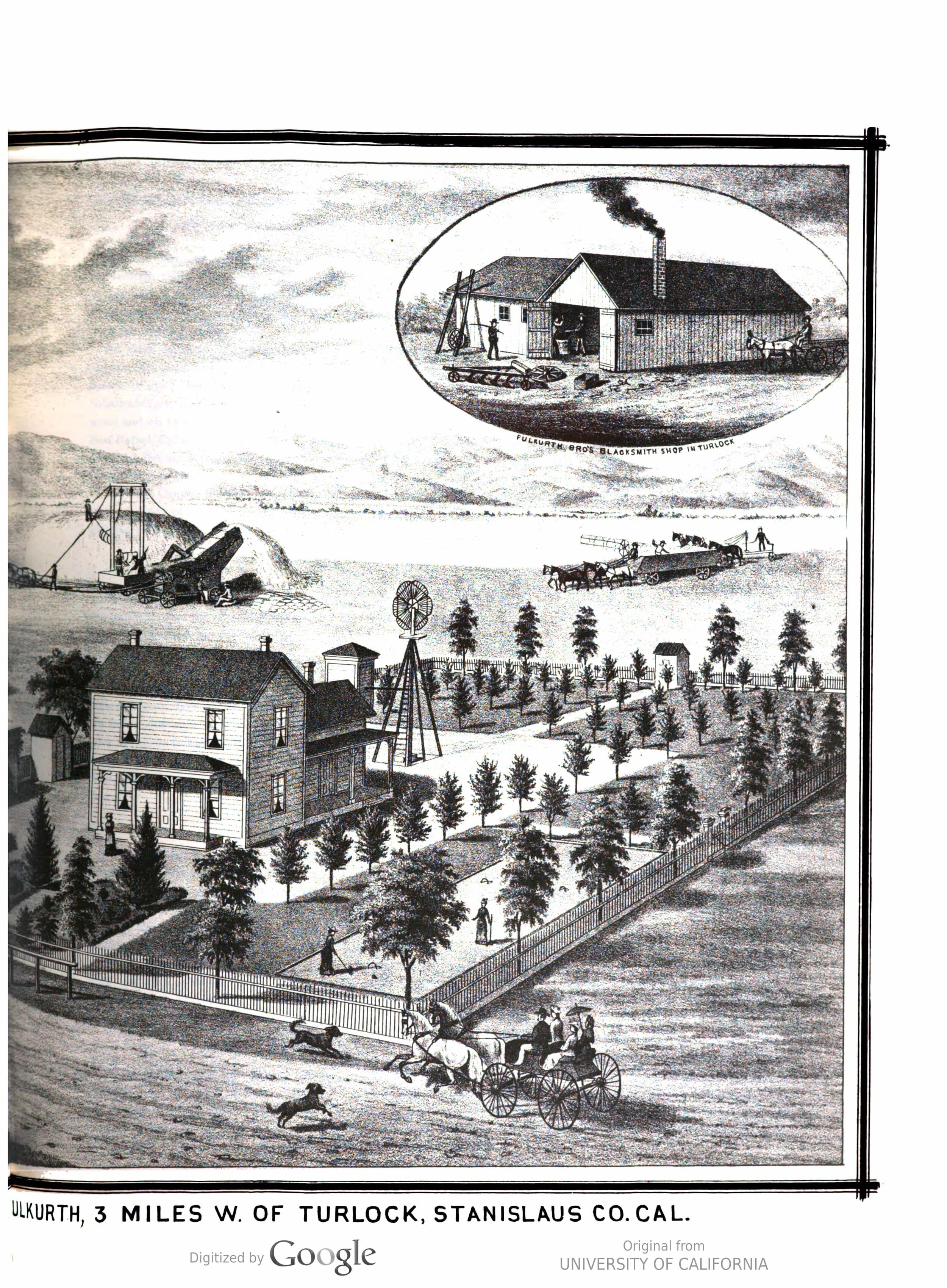

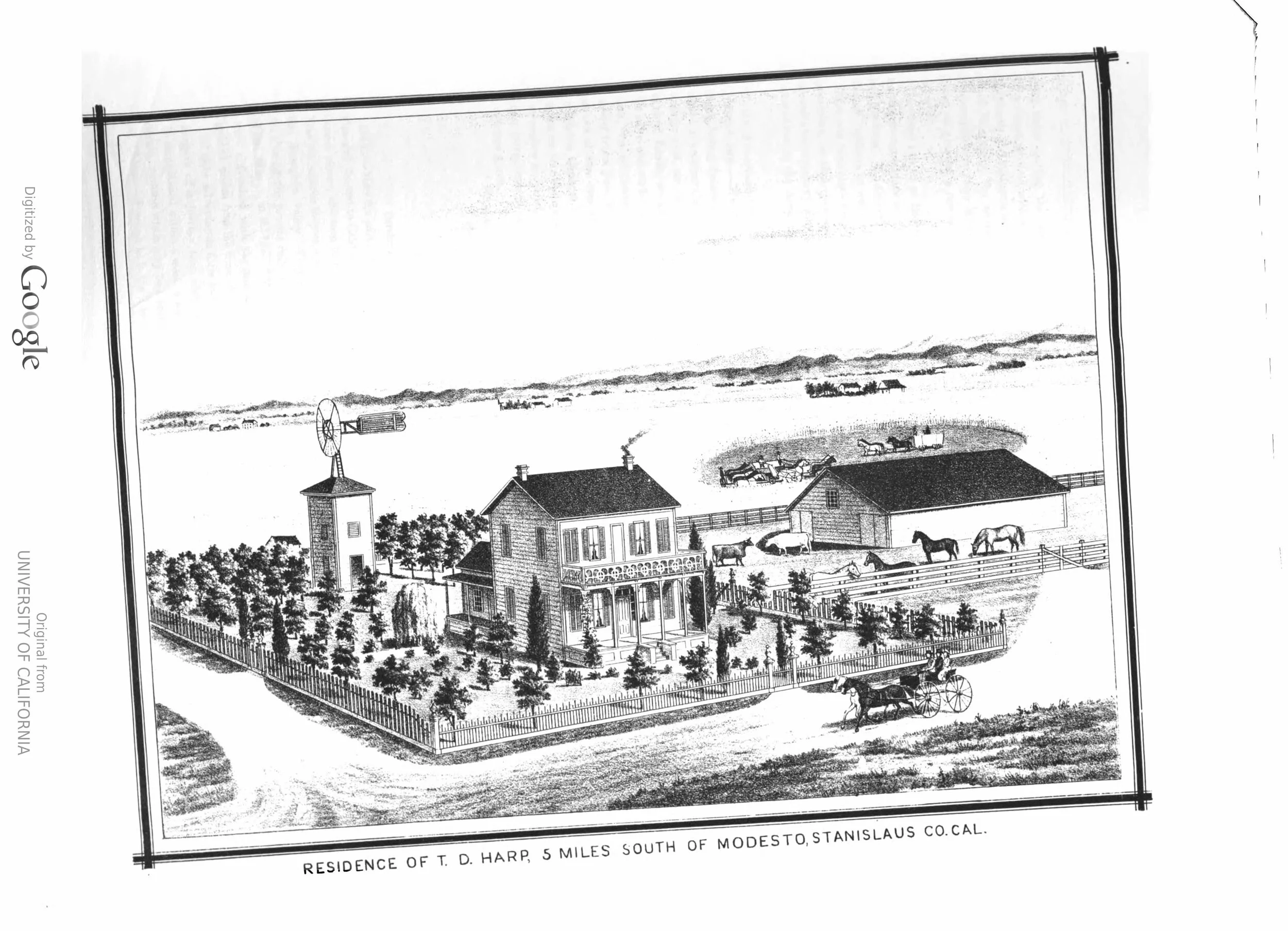

L. C. Branch’s History of Stanislaus County, California, published in 1881, was an elaborate production: a folio volume printed on fine paper, it included eight maps and charts, sixteen portraits of prominent citizens, seventeen wood engravings, and two hundred “lithographic views.” In it, Branch celebrated the “elastic energy, unconquerable enterprise, and unsurpassable progress” of the county’s people and cheered their county seat, Modesto, as “one of the best business and progressive towns on the Pacific coast.” In the drawings of farms, ranches, town residences, and places of business, everything is laid out with a geometrical orderliness, every aspect of the built landscape is tidy and neat.

Carver Residence, in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 92.

Turner Home, in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 34.

Beside handsome Victorian homes, fountains burble and windmills stand silent watch. Ladies play croquet on immaculate lawns as gentlemen arrive driving buggies pulled by prancing horses, greeted by capering dogs. In the background, a few workers bring in the harvest, using machines that puff a little black smoke into the clear air. More modest houses still have pruned shade trees, well-trimmed shrubbery, and perfect picket fences.

Saloons and Residences, in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 148.

Rogers Hall, in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 65.

Downtown stores, empty and waiting for customers, sparkle inside and out. The county court house “presents all the architectural beauty which modern art could supply,” Branch wrote, but the Stanislaus Brewery, too, was extraordinarily attractive and even Modesto’s coal gas plant had clean machines and a yard ornamented with evergreens and flowers.1

Masonic Block and Drugstore, in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 30.

The county’s prosperity had sprung from wheat, the railroad, and the work of only the past decade or so. In the blink of an eye, Stanislaus had become “the banner wheat county in the state.” Kelso, too, marveled at the wheat. “I suppose that it is the greatest wheat country of its size in the world,” he wrote. “Very little of anything else is cultivated.” Farmers planted vast farms, sometimes over 10,000 acres. They plowed with gang plows, sowed with machines, and harvested using headers pulled by eight horses and cutting sixteen-foot swaths through the grain. “Wheat here is everything. Nothing else of a profitable nature can ripen before the dry weather sets in. The people sow wheat, and harvest wheat, and thrash wheat, and haul wheat, and sell wheat, and buy wheat, and ship wheat, and eat wheat, and feed wheat, and make hay of wheat, and talk of nothing but wheat. Entire counties are in a single wheat field. Roads run through these fields everywhere, usually upon section lines. No fences are to be seen. No stock is permitted to run at large. You may ride for days and never get out of wheat.”2

Davis Ranch, in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 60.

Ranch of Fulkurth Bros., in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 42.

Modesto quickly sprouted on land purchased by the Union Pacific Railroad in 1870, became the county seat in 1872, and by 1880 had over 1800 people. Though he lived in various places in the county depending on where he was teaching, Kelso participated in the civic life of Modesto. He earned a lifetime teaching certificate from the state, became involved in the Teachers’ Association, and participated in teacher training conferences in the town. He was the poet laureate for the Modesto July Fourth celebrations in 1876 and 1884. In the 1870s, Kelso wrote for and helped edit the Modesto Herald, a Republican newspaper in a strongly Democratic town and county.

Residence of T. D. Harp, in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 40. Kelso worked for Harp in the 1870s.

Modesto Herald Office, in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 26.

Teacher, Preacher, Soldier, Spy Figure 15.2: Teachers’ Institute, Modest, California, c. 1880. Kelso: far right, second row. Photo courtesy McHenry Museum, Modesto, California.

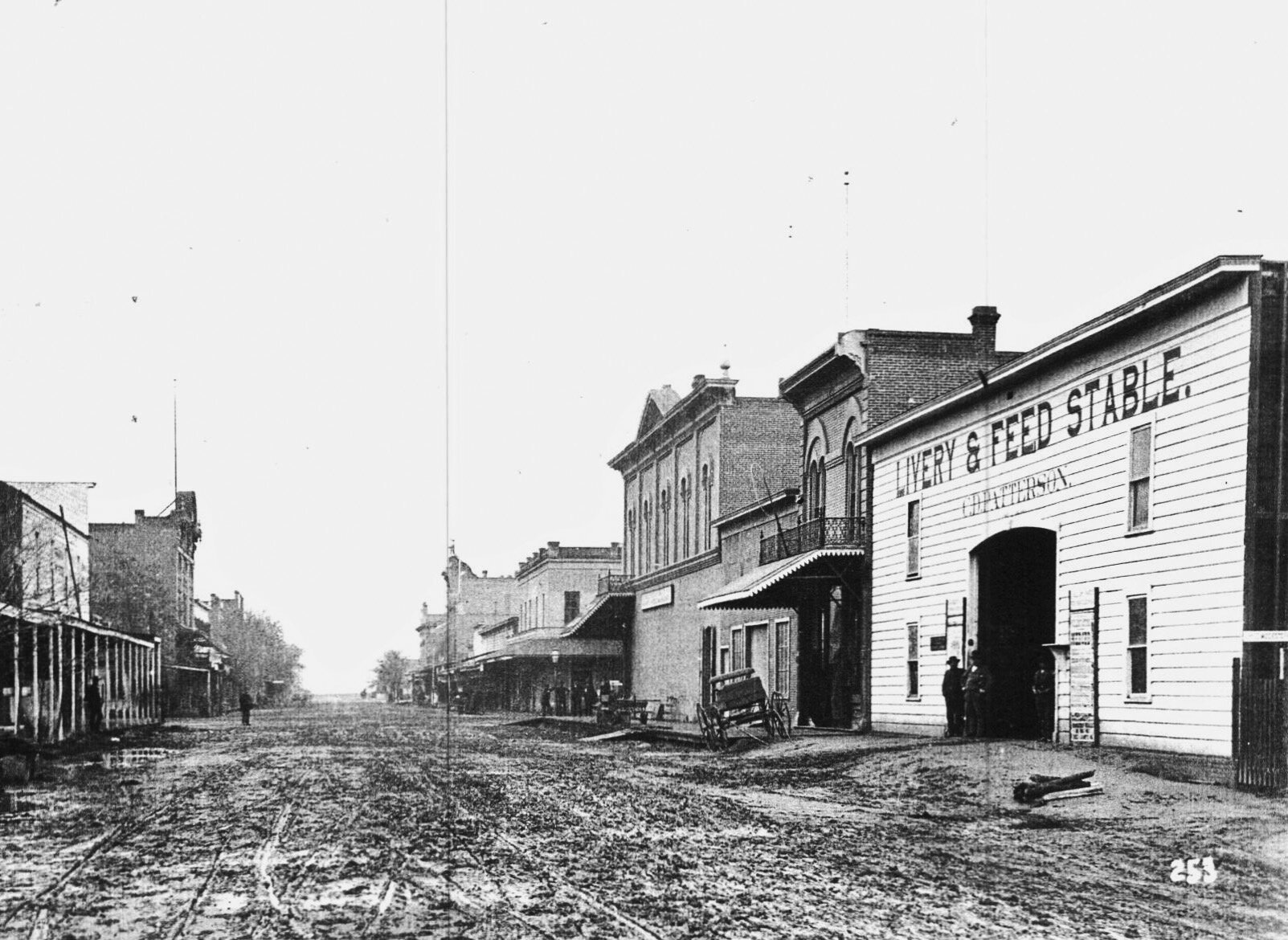

Kelso’s Modesto, however, was not quite the clean, prosperous, and peaceful town depicted in the 1881 county history’s pretty drawings and enthusiastic descriptions. The Stanislaus County seat had in fact achieved a notorious reputation by the late 1870s.

Teacher, Preacher, Soldier, Spy Figure 15.3: 10th Street, Modesto, California, c. 1875. Photo courtesy McHenry Museum, Modesto, California.

The Herald reported in August, 1879 that “[f]or years past Modesto has been the rendezvous of gamblers, thieves, rollers and gentlemen of that ilk, who seem to entertain the opinion that they were secure from molestation by police officers and could ply their nefarious business without fear of the law. They said that when they could not remain anywhere else they could come to Modesto and be safe from any annoyance. Dance houses and opium dens loomed up in the distance and these places were thronged nightly by these human hyenas, their orgies being kept up until a late hour. Drunken men were rolled and robbed on the streets, ladies were insulted, young lads were enticed into their dens of iniquity and numerous offenses committed.” The summer of 1879 was especially bad because a bumper crop brought farm laborers to town flush with cash and the card sharks and prostitutes who wanted to relieve them of it. Solomon Elias, who grew up in Modesto and later returned to be the city’s mayor and historian, recalled that the “liveliest mining camp possessed no edge upon Modesto in the years from 1879 to 1884. . . . Money was spent with a recklessness and prodigality that baffled understanding.” The saloons on Front Street, the dance halls on Eighth and Tenth Streets, the grog shops in the alleys, and the opium dens in the Chinese section ran “wide open” and “at full blast.” Young and old from the farms came to town to slum with the “painted ladies” and “the most daring sports, gamblers and saloon hangers-on that could be gathered together in the state.” The saloons controlled politics in Modesto and in the county. Their leader was the Front Street boss, Democratic Party power broker, and owner of the Marble Palace Saloon, Barney Garner, who had shot and killed gambler and brothel owner Jerry Lockwood in 1871. When the Stockton Herald called Modesto “a God-forsaken and devil-ruled town,” it was repeating a commonplace, not reporting news.3

On two occasions, local citizens, tired of the carousers, the brawlers, and the drunks, the pimps, the whores, and the opium smokers, tried to take matters into their own hands. According to one account, the vigilantes met in an old warehouse on the outskirts of Modesto; according to another, in the town’s Odd Fellows’ hall. Members—and there were about 150 of them—“were the most substantial and prominent farmers and businessmen in Modesto and vicinity.” They were called to night meetings by messengers or by coded messages posted in downtown shop windows. They came armed, singly or in pairs, and met in darkness. “They were led by a ‘Captain’—a man of family, of property, a farmer in whose veins flowed Revolutionary blood, for his ancestors had fought under Washington and his kin had been in the Civil War. An advocate of law and order, in private life he was known as a law abiding citizen. The Vigilantes gave implicit confidence to his leadership of them.” A merchant served as the group’s secretary. On Thursday evening, August 14, 1879, they assembled wearing black masks and carrying shotguns and revolvers, marched down Tenth Street, and deployed in front of Sullivan’s dance hall. The Captain called out Sullivan, and when the owner appeared, he was ordered to close his place and leave town the next morning. Then “pandemonium reigned in the house,” with the barflies scattering and frightened “scantily dressed” women running off down the street. The vigilantes then marched to Johnson’s dance hall on the corner of H and Eighth streets, and repeated the performance. After that they hit the saloons on Tenth and Front streets and the grog shops in the alley between G and H streets. The Captain and his crew finished their night’s work in Chinatown. “Ropes were placed around some of the opium shanties, and with the combined tugging of the Vigilantes they were razed to the ground.” From the ruins the masked men gathered up “pipes and other smoking paraphernalia, fan tan layouts and faro tables,” and made a bonfire on the public square.4

The next morning the exodus of riff raff heading for the train station included a man named John Kelley, who was so drunk that he had to be dragged by two friends. Kelley had made it part of his business “to entice young girls into houses of infamy.” In the crowd watching Kelley being dragged along the dusty street was John Speekman, an old man from the mining town of Sutter Creek who had left his sickbed and walked the seventy miles to Modesto. Speekman’s missing fifteen-year-old daughter had been spotted in a Modesto brothel, and Kelley had put her there. Speekman leapt from the crowd and with his pocketknife stabbed Kelley several times in the stomach. Kelley’s two friends left him on the station’s platform after the train conductor refused to let the bleeding man aboard. He died four days later. The locals declined to indict Speekman; Kelley, they thought, got what he deserved.5

Modesto’s two main newspapers, the Herald and the Stanislaus News, both applauded the vigilantes’ efforts. “The work they have thus far accomplished,” the editor of the News remarked, “is undoubtedly a good one, and will receive the sanction of all citizens. We have no doubt those who are in charge of the movement will use due caution and see that it does not extend any farther than public morality requires, as well as the laws of the state justify.” But the effects of the 1879 raid lasted for only a few months. The saloon faction kept its tight grip on politics and law enforcement, and soon things returned to normal: “There were the brutal pistol duels, the customary bruising, drunken brawls and fights, the wide open gambling, the highway robbery, pocket picking, petty thievery, and thuggery, and all the other accompaniments of saloon and tenderloin control.”6

In 1884, a more controversial exercise of vigilante justice threw Modesto and Stanislaus County into turmoil. The catalyst was the arrest of two men accused of raping two young girls. John J. Robbins, sixty years old and with a flowing white beard, came to town in 1882 and hung out a sign as an attorney. “His clientele did not keep him very busy, and soon it was observed by persons in the vicinity of his office that he was fond of little girls, ‘and often asked them into his office, petted them and giving them candies told them stories.’” John H. Doane, 57, who had spent some time in prison for shooting a man in Tuolumne, had a small saloon about six miles from town and seems to have been connected to a third man, a photographer named Albert Beck, who was accused of taking pictures of naked young girls.

Residence and Saloon of J. H. Doane, in L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), after p. 164.

All three were arrested, and Robbins and Doane were charged with having taken criminal liberties with sisters Lulu and Dora MacCrellish, whose ages are given as eleven and fifteen in one account or nine and “over ten” in another. The MacCrellish family, however, were considered stupid, profligate, and “shiftless in the extreme”; the parents had let Dora sleep at Doane’s place for three nights and had been chased out of another town for suspected blackmail, a scheme involving their daughters.

Doane was released on lack of evidence (and it was claimed that Dora had given her consent). Lulu at Robbins’s trial claimed that the old man had a distinctive tattoo on his body, but he was acquitted when, after stripping for the jury, no tattoo was found. “There was subdued whispering among small knots of men gathered at the street corners.” At one point, a mob formed and some men brought a rope intending to have “a necktie party,” but nothing came of it.7

Not long after Robbins was released, on March 1, 1884, three notices were sent by unknown persons signing as the “San Joaquin Valley Regulators” to Doane, Robbins, and John MacCrellish: “Leave this county within ten days, fail not on pain of death.” The MacCrellish family, after begging for (and receiving) funds to pay for their travel, did leave. Robbins at first scoffed at the threat and posted a $100 reward for information on the identities of the Regulators, but then he left too. Doane defied the Regulators. He brought the letter to a Modesto saloon, vowed to fight, and then, after getting suitably liquored up, staggered up and down Front Street, yelling challenges into the dark. He drew two pistols on a passing farmer, but bystanders prevented bloodshed.8

On Wednesday night, March 19, 1884, the San Joaquin Valley Regulators assembled and put on their masks. Twenty-five went to the nearest bridge and waited. Another twenty-five, on horseback, made their way up Waterford Road to Doane’s saloon. Others were stationed along the roads between the two points. The plan was to capture Doane, put a noose around his neck, and hang him from the bridge. Seven or eight Regulators, masks pulled up and weapons drawn, entered the front door. Doane was there, playing cards with three other men. The Regulators shouted to the men to put their hands up. Three of them did, but Doane tried to bolt to his bedroom to grab his gun, and a shotgun blast dropped him to the floor, where he died.9

Two days later a notice was posted and published, signed by the San Joaquin Valley Regulators, listing twenty-five names and warning them all, along with “all gamblers and persons without any visible means of support,” to leave Modesto and never return, “under peril of your lives.” The notice concluded: “Remember Doane’s fate.” The train leaving town was crowded the next morning. On Saturday evening, April 7, the Regulators paid another visit to Chinatown, and again destroyed the opium dens. Ten days after that they issued another edict, this one directed to the disreputable people who had been driven out but were still said to be “lurking in the vicinity of Modesto,” waiting for things to cool down so they could return: “Now, therefore, all such persons are ordered to leave Stanislaus County immediately and never return, under penalty of death, and all persons are forbidden to harbor anyone under the same penalty. All gamblers, pimps, and prostitutes are forbidden to come into Stanislaus County. Remember Doane’s fate.”10

This time, however, the opponents of the Regulators pushed back. Some of the names listed in the March 21 notice belonged to the wild young sons of prominent families. And saloon boss Barney Garner publicly denounced the vigilantes. When the Regulators then threatened Garner directly, he had the letter published and decried in the town’s Democratic paper, the Stanislaus News. Other newspapers in the region, too, criticized the vigilantes. The San Francisco Daily Alta California deplored the “mob government” ruling Modesto. The Stockton Herald and the Morning Union condemned the Regulators’ “reign of terror” and called for a rival “vigilance committee” to rise up and oppose them. Or perhaps California’s governor should call out the National Guard. “Stanislaus County ought to be disorganized and its territory divided up and attached to neighboring counties,” the papers concluded. The Regulators, in a final notice issued on April 25, apologized for nothing, saying that they had made the town and the county safer and better.11

Political tensions were directed back into more conventional channels that summer with the move to incorporate Modesto and create a more robust local government with five trustees, a clerk, a treasurer, and a city marshal. At a raucous mass meeting at the beginning of August, the debate between the Democrats and the Republicans almost produced a riot, but both sides ended up in the same place. As Sol Elias, the later mayor and chronicler, wrote: “To the anti-Vigilante electorate the plea was made that incorporation would save them from the Regulators. To those who favored the Regulators, the argument was made that incorporation would obviate the further necessity for the activities of this extra-legal body.” The vote for incorporation passed by a large majority. With the new government, the saloons and the brothels did not immediately disappear, but Modesto gradually started to become a more orderly and law-abiding place—especially after Front Street boss Barney Garner, reaching for his pistol, was shot dead by the marshal.12

1 L. C. Branch, History of Stanislaus County, California (San Francisco, CA: Elliott and Moore, 1881), esp. 109-112.

2 Branch, History of Stanislaus County, 10; D mss 12: 25, 27-8.

3 Modesto Herald, quoted in Tinkham, History of Stanislaus County, 144; earlier articles by Elias quoted in Tinkham, 101 and Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 293; Tinkham, 139 (Garner killing Lockwood); [No title], (Grass Valley, CA) Morning Union, May 4, 1884, 3, reprinted from the Stockton Herald (“God-forsaken”). See also Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 296.

4 Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 298-9; Tinkham, History of Stanislaus County, 145. See also “News of the Morning,” Sacramento Daily Union, Aug. 16, 1879, 2; “Coast Items,” (Healdsburg, CA) Russian River Flag, Aug. 21, 1879, 1; [no title], (San Francisco, CA) Pacific Rural Press, Aug. 232, 1879, 121; “The Chinese Must Go,” Santa Barbara Weekly Press, Aug. 23, 1879, 1.

5 Tinkham, History of Stanislaus County, 141-2 (and quotation); Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 300-1. The story was reported in “A Seducer Killed,” Santa Barbara Weekly News, Aug. 23, 1879, 1.

6 “The Modesto Vigilantes,” (San Francisco, CA) Daily Alta California, Aug. 28, 1879, 1, quoting the Stanislaus News; Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 304-5.

7 Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 307 (quotation); Tinkham, History of Stanislaus County, 143.

8 Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 310; Tinkham, History of Stanislaus County, 147-8.

9 Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 311-12; Tinkham, History of Stanislaus County, 148.; “San Joaquin Valley Regulators. A Saloon-Keeper Near Modesto Shot by Armed Men,” San Francisco Bulletin, March 21, 1884, 5.

10 Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 313-14; Tinkham, History of Stanislaus County, 148-9 (quotations). See also “San Joaquin Regulators. A List of Persons Ordered to Leave Modesto,” San Francisco Bulletin, March 24, 1884, 1; “Murderous Regulators,” (Grass Valley, CA) Morning Union, March 25, 1884, 1; “Modesto Regulators,” Mariposa Gazette, March 29, 1884, 2.

11 “Mob Government,” (San Francisco, CA) Daily Alta California, March 23, 1884, 3; the (Grass Valley, CA) Morning Union reprinted and endorsed pieces in the Stockton Herald; May 4, 1844, 3 (“reign of terror”); : [no title], April 26, 1884, 1; “A Mob Law Community,” March 29, 1884, 2 (call for Stanislaus to be disorganized); and see the Union, [no title], May 9, 1884, 2. On the young men from good families: [no title], Morning Union, April 2, 1884, 2; “Sad Indeed,” Santa Cruz Sentinel, May 1, 1884, 4, rpt. from Merced Argus. Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 303; Tinkham, History of Stanislaus County, 149.

12 Elias, Stories of Stanislaus, 326 (quotation); Tinkham, History of Stanislaus County, 102, 140 (death of Garner). See also “Excitement in Modesto,” Sacramento Daily Union, July 10, 1884, 1.